General Versatility

Specialize or generalize? Artificial Narrow Intelligence (ANI) or Artificial General Intelligence (AGI)? Expertise or Versatility? The age-old tensions may be false dichotomies.

There’s familiar tension between generalization and specialization. Those who generalize tend to learn and experience a broad field of knowledge, while those who specialize intentionally limit their field of knowledge in order to go deep.

Generalists often criticize specialists for lacking awareness about even the simplest things outside their narrow domain. Specialists criticize generalists for only skimming the surface of knowledge, lacking depth about anything.

Addressing a common criticism that scientists study nature so minutely they can’t appreciate its beauty, Theoretical Physicist Richard Feynman said:

“To those who do not know mathematics it is difficult to get across a real feeling as to the beauty, the deepest beauty, of nature ... If you want to learn about nature, to appreciate nature, it is necessary to understand the language that she speaks in.”

Feynman points us past the perceived dichotomy, suggesting there may be more to this tension. Some hunt the Universal and some stalk the Particular. We too rarely appreciate the strengths of the other, or to realize we may be thinking in caricatures.

Might integrating these supposed tensions create an entirely different approach to knowledge? To attempt this we’ll need to pay less attention to the very different things the universalist and the particularist pursue, and focus, instead, on recognizing the patterns they both share—patterns of pursuit. We’ll need to focus on first principles to explore common ground.

In recent weeks I’ve reviewed a lot of job descriptions and assessed how some AI tools made connections between data points in job descriptions and variations of my résumé. Unfortunately I had no real observability into these systems. All I could see was (1) the raw data in the job descriptions, (2) raw data in the résumé variations, and (3) the recommendations generated as output from a hidden comparison.

Using this kind of AI is like making a meal with a pressure cooker—I can see the ingredients I put in and the (hopefully edible) results that come out, but the cooking process itself is completely hidden.

Many of us may celebrate this and celebrate the magic of such an experience. Those of us who care deeply about data—how we can trust it, how it’s interpreted, and how well the results align with the intentions designed for the system—aren’t content with a purely magical experience.

We want observability so we can assess and adjust the data and the algorithms that learn from it and produce new data we will inevitably act on.

If the data that goes in is flawed or the learning process misunderstands the data or does something inappropriate with it, the results will be a mess—like a throwaway meal from pressure cooker, or a missed job opportunity.

The job descriptions I looked at pointed to a strong tendency to favor specialization over generalization. This was the case with approximately 90% of the job descriptions I reviewed.

For the 10% that seemed to favor a more generalized background it was unclear what percentage of these were written by people who didn’t understand the specificity the team might be looking for, and what percentage were truly hoping to attract candidates who had developed strong general knowledge.

Curiously, a contrasting intention was ubiquitous in these job descriptions. They invariably ended with statements encouraging diversity and strong commitments to attracting a wide range of backgrounds and experiences to create a well-balanced company culture.

Why the strong desire for specialists?

When people set out to build teams, there’s a tendency to think in reductionistic terms. We end up thinking about titles and positions and functions in a structure that has discreet points. Each of these “nodes” presumably represents a unique, specialized function. We write a job description with this “ideal” in mind and we end up “fishing” for very specialized people.

This leads us to narrow of our focus even further when interviewing because we know we must triage the massive inputs of applications, and then have a way to discern a good hire from one we should avoid. We want those we hire on our teams to make an impact in the company structure. So, when writing a job description we consider what we think we know about our operating environment:

- The industry and our business appear complicated.

- The company culture and structure appear complicated.

- The solutions we design and build appear complicated.

Therefore we think we need experts who understand the complicated workings of all these things and can scientifically orchestrate the complicated machinery to achieve success. Mathematics and logic are realms where understanding leads to expertise. Learning and building teams are realms where complexity reigns, and expertise won’t cut it.

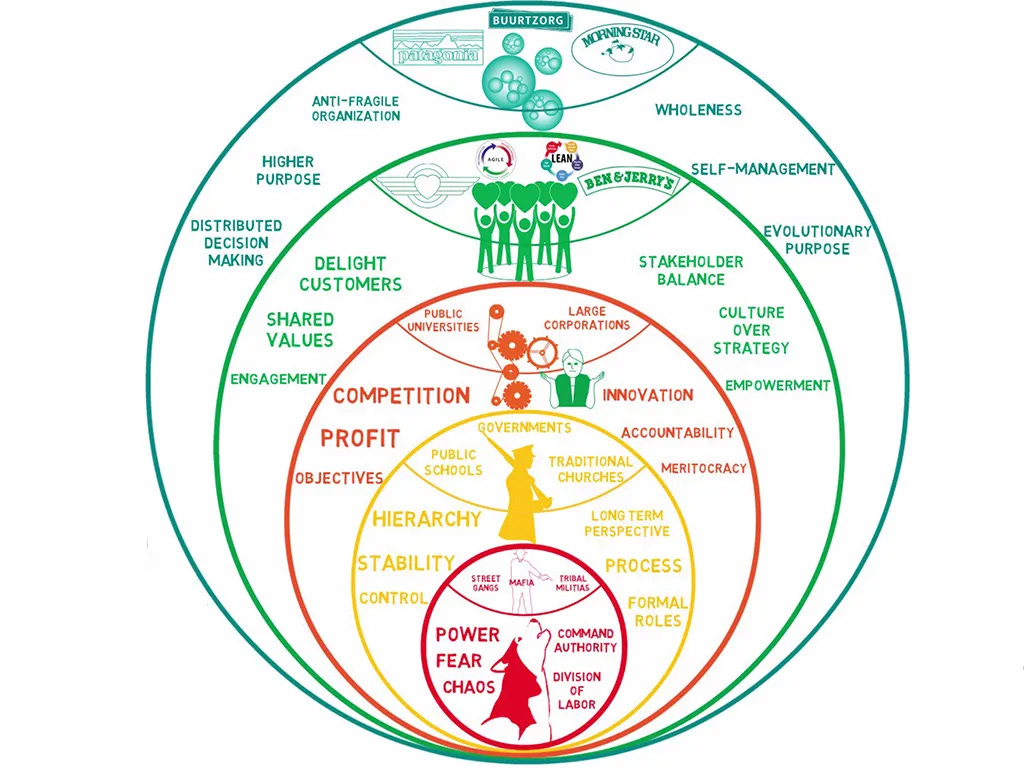

David Snowden’s Cynefin Framework and Frederic Laloux’s Culture Model from Reinventing Organizations both provide excellent insights about assessing environments and what kinds of decisions must be made, or even can be made, in each. I’ll share more about the power of these insights in the future.

For now I’ll summarize two environments—the complicated and the complex.

- Complicated contexts involve “known unknowns”. There may be multiple “right” answers, but they can be figured out by people who have the right knowledge or expertise to understand how the pieces fit together. An automobile engine is an excellent example of a complicated system. Leaders must sense, analyze, and respond.

- Complex contexts involve “unknown unknowns” and the “right” answers can’t be figured out by experts. Experiments and probing are ways to uncover patterns and pathways through the complexity. We learn by failure and success, and that learning propels us forward. Leaders must probe, sense, and respond. The way emerges from the patterns being learned and cannot be imposed.

Snowden believes most businesses operate in complex environments but don’t realize it. They operate mostly as if they believe things are just complicated. He issues a stern warning for leaders in such situations:

As in the other contexts, leaders face several challenges in the complex domain. Of primary concern is the temptation to fall back into traditional command-and-control management styles—to demand fail-safe business plans with defined outcomes. Leaders who don’t recognize that a complex domain requires a more experimental mode of management may become impatient when they don’t seem to be achieving the results they were aiming for. They may also find it difficult to tolerate failure, which is an essential aspect of experimental understanding. If they try to overcontrol the organization, they will preempt the opportunity for informative patterns to emerge. Leaders who try to impose order in a complex context will fail, but those who set the stage, step back a bit, allow patterns to emerge, and determine which ones are desirable will succeed. — Snowden and Boone, HBR (2007)

Trails and entrails

To use a more visceral metaphor, if my intestines have a problem that requires an operation, I want to know that the surgeon who will perform the delicate and life-saving tasks is an expert in this particular procedure. I don’t want a general practitioner to lead that effort.

If, on the other hand, I’m navigating a forest landscape through mountainous terrain with unpredictable weather, ecological shifts, and uncertain food and water sources, and possible injury, I want to be led by someone who knows how to navigate complex environments and who isn’t paralyzed by the emergence of unknown unknowns. I want a leader who tests the environment, senses the right direction, and moves quickly as that leader turns unknowns into clarity.

The Fire Swamp

If you’re familiar with the classic film The Princess Bride, there’s a nearly perfect scene that demonstrates the effectiveness of this kind of leadership in complex environments.

To escape the pursuit of the evil prince, Wesley and Buttercup enter the Fire Swamp. It’s a dark landscape overgrown with trees and vines, shrouded in mystery and legend. Buttercup says, “We’ll never survive.” Wesley responds, “You’re only saying that because no one ever has.”

Somehow (with no survivors) they’re familiar with the dangers of the Fire Swamp: bursts of flames, Lightning Quicksand, and Rodents of Unusual Size. As they make their way through the swamp, they encounter each of these risks by failing into them. Leaders in complexity must probe and learn quickly from failures. Wesley finds the patterns that make him able to identify the dangers and thus avoid them in the future. He learns from each failure and improves as he senses and responds, continuing to find his way through the swamp with greater and greater confidence. As the two protagonists journey together his optimism keeps them going, and he shares as he learns.

Although the value of this kind of leadership feels very fresh and new, it has been around a long time. In 1916, for example, a well-known professor of literature framed the generalist/specialist debate starkly when talking about the impossibility of reading English at Cambridge University.

Reading Q

In his lecture series On the art of reading, Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch—known to his students simply as `Q`—made a strong argument against specialization. While the specialist has the presumed advantage of diving more deeply into an area of inquiry than the generalist, the specialist sacrifices more comprehensive abilities and opportunities, he claimed.

Q was disturbed by a problem that has exponentially increased in the past hundred years. The sheer volume of information available to a reader in 1916 made it difficult to navigate. Q urged his students to seek wisdom in order to attain the skills of discernment necessary to avoid the pitfalls all around them.

Pursuing knowledge is complex because it’s constantly growing. Somehow we have to find ways of crossing that complexity generally or reducing it through specialization.

If you crave for Knowledge, the banquet of Knowledge grows and groans on the board until the finer appetite sickens. If, still putting all your trust in Knowledge, you try to dodge the difficulty by specialising, you produce a brain bulging out inordinately on one side, on the other cut flat down and mostly paralytic at that: and in short so long as I hold that the Creator has an idea of a man, so long shall I be sure that no uneven specialist realises it. The real tragedy of the Library at Alexandria was not that the incendiaries burned immensely, but that they had neither the leisure nor the taste to discriminate. —Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch

I think of a trail in a wilderness I’m learning to know. Each new decision point sets a direction and a curriculum of new things to learn, uncertainties to explore. The complexity problem Q and his students wrestled with was as if each decision point amplified a continually expanding set of potential pathways—unless they forced themselves to become as narrow as possible in their focus. Then the expansion rate of this narrowed knowledge seemed to slow. It felt manageable. However, in doing so, they miss the forest for the trees, so to speak.

To restate Q’s argument a little, a person who achieves specialization in ancient fragments of Plato’s Republic doesn’t necessarily mean they’ll later be able to become an expert at trail racing. The one specialization does not confidently lead to the other—but it may.

Imagine, by contrast, a person who becomes an expert at learning new things. They are knowledgeable and skilled in a more general sense that makes it possible to acquire expertise in a wide range of domains. That person could more confidently become an expert at both Plato’s Republic and trail racing, as well as a number of other things.

In doing so they become versatile because they can be placed in a complicated environment and learn to be an expert at something they didn’t previously know. They are equally comfortable in complex and rapidly changing environments; they know how to navigate and learn.

The dangers of the silo

As a counterpoint, let’s take a deeper look at Q’s conception of the specialist’s approach to solving the impossible challenge of handling the glut of knowledge.

…to read all the books that have been written—in short to keep pace with those that are being written—is starkly impossible... —Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch

This approach creates new problems, according to Q, and serious ones. It generates a “silo effect” where each person or specialized group only knows a small piece of the larger puzzle of reality. It has massive implications for decision-making (not to mention organizational structure).

Imagine the trail metaphor again. You could intentionally travel the same 5000 meter path over and over until you know all kinds of details about the wooded landscape and are an expert at that 5000 meters. Doing this you risk missing the fact that the woods are only 3000 meters from the seaside. You can hear a faint, persistent sound but don’t really know what is making it. Perhaps it’s just the wind.

If you want to experience a contemporary exploration of the “silo effect” watch Apple TV’s “SILO”. By the end of the first season you’ll feel viscerally that this experience of reality poses existential dangers.

The specialist’s impact is necessarily reductive rather than expansive.

Q’s solution — decision-making as art

Q concludes that the answer comes through decision-making as art. We decide what is worth learning. We purposefully build a curriculum for growth of a certain kind. Q is hoping for growth that results in thriving humanity, for knowledge that benefits others, that produces light in a dark world.

We must select. Selection implies skilful practice. Skilful practice is only another term for Art. —Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch

If purpose and passion are clear, this ‘skilful practice’ can be built by creating a curriculum for growth that integrates the things that bring about ‘traction’ and avoids those that create ‘dis-traction’. Generally what we might call being “fully alive” becomes a real possibility. For more on becoming “Indistractable” I recommend Nir Eyal’s excellent book on the topic.

Eric Davis, a Navy SEAL instructor turned entrepreneur, describes this kind of ‘skilful practice’ as mastery—“becoming an expert at becoming an expert”. It’s really an integration of art and science that focuses on practicing customized tactical standard operating procedures (TSOPs) that can adapt to the complexities being experienced.

When a finely-tuned athlete or musician performs consistently at the highest level, some will call it ‘art’ and others ‘science’ but the reality is that it’s both. The long journey to reach that level of performance required optimizing the learning and practice and going deep into the knowledge of details most people would find too much to understand.

Seeing the combination of these supposed dichotomies in the study of performance, it should be obvious that reality is more complex than we think. We can move from Q’s either/or presentation to a more integrated view of the generalist-specialist dilemma.

For the specialist, learning has a narrow field, but if it’s done reflectively using metacognition, a specialist can dive deep while simultaneously understanding how he or she is learning. This general knowledge can then be applied to other areas of specialty as needed.

For the generalist, understanding metacognition empowers them to learn in any direction. The challenge then becomes one of selection, as Q puts it. What are we learning today? What opportunities for learning will emerge tomorrow? Are there areas of specialization we want to intentionally pursue using our general knowledge of how to learn? The generalist becomes capable of specialization as needed.

Brief introduction to the complexity curriculum

What kind of curriculum, or practice, does crossing complexity require? I’ll be unpacking a lot more of this in future posts, but for now, here’s a taste of what’s to come.

We must accept that uncertainty and ambiguity are ever-present. Like the concept of risk, we ignore or minimize it to our peril. We must navigate through uncertainty and ambiguity with intentionality.

To borrow a concept from product management, the “user story” is a way to describe intentionality.

The user story structure:

As a user… (who)

I want to… (intention)

in order to… (impact)

Example:

As a user of the product I want to be able to share my ideas with a community of readers in order to create impact in the lives of my readers.

This kind of user story provides enough intention that we can explore possibilities and design solutions that move us toward the successful realization of that intention.

Using the same framework we could look at our lives. Here’s an example that expresses something of my purpose as I understand it today:

- As a human being (as me) I want to build creative teams who collaborate well in order to create a brighter future.

Naturally, yours will be quite different. Please comment if you’re willing to share.

Having grabbed hold of at least a version of our purpose, we can consider the question “What would have to be true…?” as we explore the complex dynamics around moving and growing toward the practice of this purpose. IDEO’s Roger Martin and Jennifer Riel have a lot to say about this question in their writings, which we’ll look at again in more detail.

Finding our way will require experimentation and teach us to become familiar with failure. We’ll need to learn how to fail without quitting our purpose.

We can then choose (or ‘select’ to use Q’s diction) the practices that are important to our curriculum in order to move us toward mastery that’s aligned with our purpose and passions.

###

If this post has sparked questions or thoughts, please comment. I’ll gladly consider any feedback to include in future posts. Thanks for reading!

Crossing Complexity is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.