Creating the future: innovation through exploration

Some of my Icelandic and Norwegian ancestors embraced the opportunity to explore the unknown. They believed in a better future and they worked to create it—at times risking their lives to do so.

For them—as for the rest of us—the future can be associated with darkness and fear. In Norse legend, the Kraken is a large squid-like creature that terrorizes the North Atlantic. Setting sail surfaces the risks hidden in the depths of what we don’t know. It’s natural to hold our breath and brace ourselves to encounter the unknown. This guarded posture reduces our ability to learn and respond. Yet, some head straight for it with anticipation, curiosity, and longing.

Why is that? If you’ve ever watched with awe as someone takes on a risky venture you can’t imagine doing, you might wonder if it’s possible to learn to relate to risk with a growth mindset, or if your posture toward risk is “fixed” at birth.

Pushing into the unknown is not an exclusively nordic trait. There are people in every culture who believe that things can get better and are willing to disrupt the status quo to realize it. Many factors contribute to our ability to take on risk, including cultural tendencies and our personal and cultural histories.

In his 1963 book Self-renewal, John W. Gardner comments on some of Alexis de Tocqueville’s insights about America:

In 1831 de Tocqueville asked an American sailor why American ships were built to last for only a short time. The sailor replied that “the art of navigation is everyday making such rapid progress, that the finest vessel would become almost useless if it lasted beyond a few years.”

Gardner then comments:

The society capable of continuous renewal not only feels at home with the future, it accepts, even welcomes, the idea that the future may bring change.

With such a mindset change ceases to be a source of fear. Imagining a future characterized by being stuck, irrelevant, or decaying with the past is far more terrifying and motivates such people to pursue making all things new—even at the risk that everything will change.

What is innovation and why is it so important?

Innovation is the act of renewing or making new. Things are constantly decaying or being eroded away, so in a real sense everything is constantly in motion. Either we’re fading away or we’re being renewed. In this light, innovation is a function of life and health. It’s not a “nice to have” but a necessity. Without it we fade out and die. That’s why it’s so important to this present moment, but also why it’s so vital for the future.

As Gardner (and de Tocqueville) observe, not everyone has a bleak view of the inevitable unknowns of the future. Some imagine possibilities, hope, and innovations like submarines that can explore the hidden depths of the ocean. Some even find cephalopods fascinating and suggest we can learn from them.

Insight from unknowns

Innovations in science and technology make it possible to explore areas that were once entirely unknown—like the deep seas inhabited by the mythological Kraken.

Cephalopods are known for their rapid response time to constant changes in their environment. It’s believed their network of distributed neurons—which account for something like multiple brains throughout their body—may account for this remarkable agility and adaptibility. Based on this, Neoroscientist Simon Spichak even suggests behaviorial flexibility could be a legitimate form of intelligence.

Structured for flexibility

Like the neural networks of a squid, human beings are part of a complex, constantly changing social fabric. Our communication and collaboration structures and processes either enhance this reality or make it more difficult to leverage the assets of connection. Cultures form along these lines and imprint attitudes toward innovation.

Unknowns create complex environments. Most businesses operate in markets with high degrees of complexity but attempt to deny or minimize that reality in order to attain power, champion expertise, and measure efficiency and other metrics deemed desirable. Then their market position gets disrupted.

Complexity is commonplace. Less common is thinking critically about the unknowns and harnessing strategy to boldly navigate toward them. (I talk elsewhere about David Snowden’s excellent Cynefin Framework for understanding different environments and the approaches to leadership each requires.)

We want to cultivate attitudes, beliefs, and practices that make it possible to chart a path through complex unknowns to bring about innovations that create a better future.

The danger of assuming past success will continue

Those of us who have once had the courage to explore, learn, and innovate—and especially if we’ve done this more than once—can experience a kind of pride that gives us a false sense of invincibility. We quickly run into the next challenge without appropriate preparation and with a fixed mindset. I’ve done this myself more than once. We’ve “done it before” and ”we’ll do it again”. We’re tempted to believe that past success once achieved can be applied to new problems with the same results.

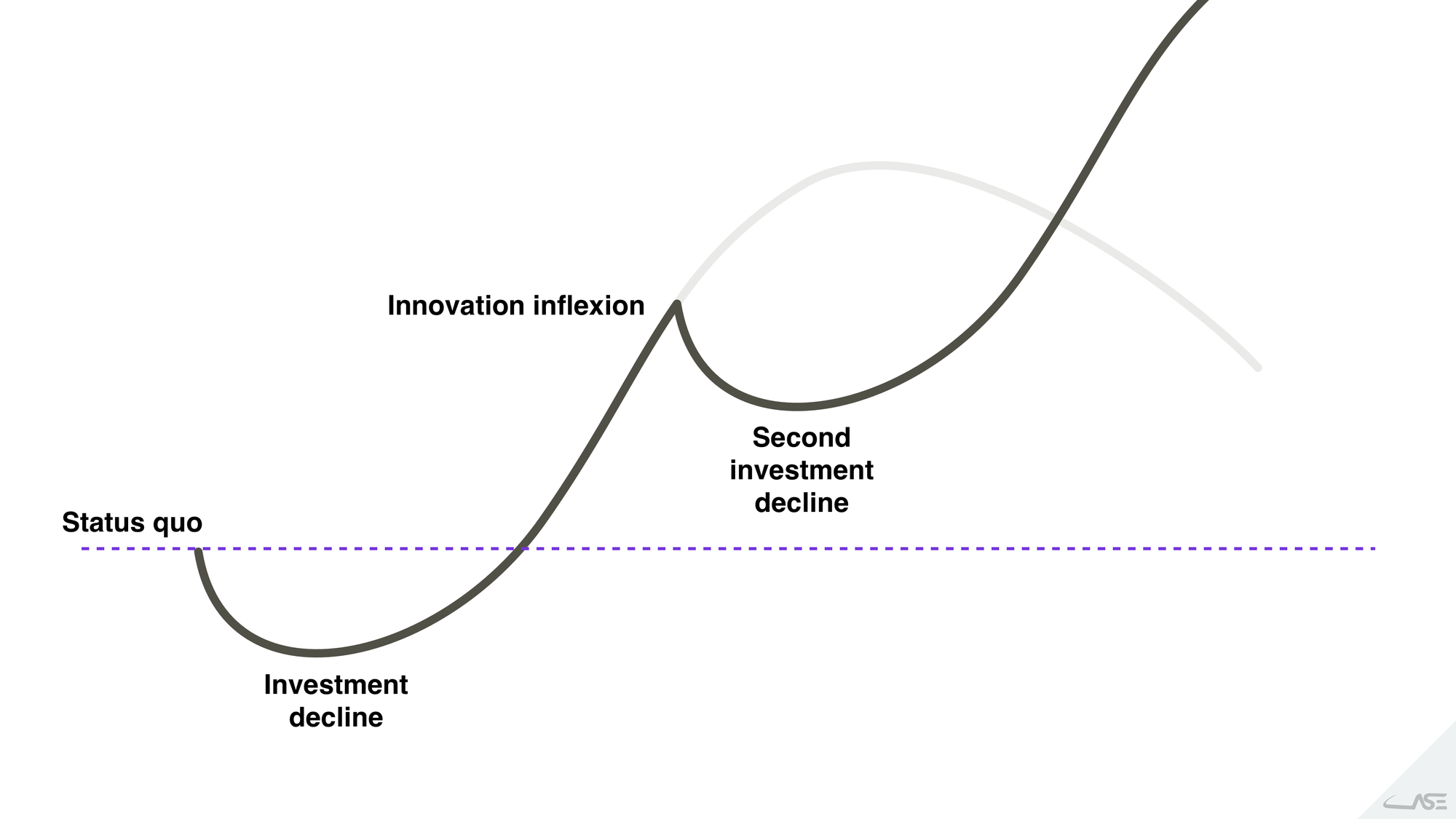

Unfortunately, applying the same approach in an entirely different context often results in degrees of failure. If we hold rigidly to what worked yesterday, we’ll eventually experience decline rather than continued innovation.

There’s a decay dynamic that causes us, our organizations, and societies to become rigid and to lose our ability or willingness to innovate. Even people and teams that are known for innovation often end up opposing the continually unfolding future at some point.

The leaders who once guided the company through initial innovations stop listening to the creative ideas of their employees because the company is a success and the ideas sound crazy. Could some of those ideas, though, be the very thing needed to continually reinvent the organization?

Simply put, when we stop having humility to listen well and learn, it’s often because we believe we’ve “arrived”, get comfortable, and stop embracing disruptive change. Discomfort makes us long for change, and comfort encourages us to stay where we are—to continue the course even when others may see it needs correction.

In his book The Comfort Crisis, Michael Easter brings engaging clarity to this dynamic, encouraging readers to strategically put themselves in challenging, uncomfortable situations at regular intervals in order to generate growth. The specifics will vary for individuals and organizations depending on many unique factors, but the principle is a powerful one that can regularly put us into a learning and innovation cycle.

In individuals, being committed to comfort means we stop learning and narrow our views. We might shift focus from the future to the past. In organizations and businesses, this means we enter a defensive posture and slowly (or rapidly) watch our relevance and market share erode. In societies, we become rigid, narrow in our views, and the very fabric of our relationships and structures begin to fall apart.

Continuous innovation requires humility

How do we avoid this all-too-common decline? How do we enter into new innovation curves?

It starts with our posture toward the future and a belief that we have an active role in bringing it about.

The society capable of continuous renewal not only is oriented toward the future but looks ahead with some confidence.

— John W. Gardner, Self-renewal (1963).

Having creative confidence doesn’t mean we’re arrogant about our knowledge, skills, or abilities. It means that despite the things we don’t (yet) know, we‘re confident we can discover and learn our way toward a solution.

An iterative process

We can use an iterative process and adjust it as context requires to discover our way toward new possibilities.

- Identify what you know, what you assume to be true, and what you don’t (yet) know. Acknowledge, too, that there are likely things you don’t know you don’t know. These can only emerge through exploration.

- Experiment and assess the assumptions and unknowns to validate and surface deeper learning. What for new unknowns to surface.

- Act by taking calculated risks (”bets”) to test possible solutions and continuously learn and adjust from feedback.

In this series we’ll discuss insights and tactics around each of these principles. Please comment or post additional questions you would like to discuss.